By Michael Phillips | Republic Dispatch

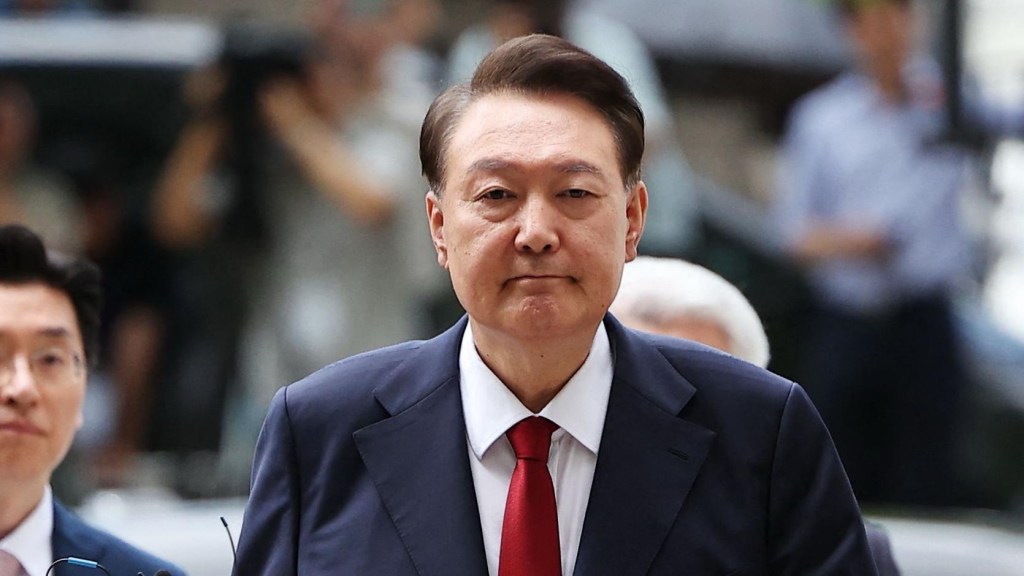

South Korean prosecutors have taken the extraordinary step of requesting the death penalty for former President Yoon Suk Yeol, accusing him of leading an insurrection following his brief and chaotic declaration of martial law in December 2024. The request, delivered during closing arguments at Seoul Central District Court this week, marks one of the most dramatic moments in modern South Korean political history.

The charges stem from Yoon’s late-night declaration of martial law on December 3, 2024—an order that lasted only hours but triggered mass political upheaval. Lawmakers defied the order, the military stood down, and the episode ultimately led to Yoon’s impeachment, removal from office in April 2025, and months-long detention while prosecutors built their case.

The Case Against Yoon

Under South Korean law, the crime of insurrection carries only two possible sentences: life imprisonment or death. Prosecutors opted for the harshest penalty, arguing that Yoon acted with “violent intent” and a desire to cling to power indefinitely.

In court, prosecutors portrayed the former president as the “ringleader” of a plot aimed at suspending democratic governance. Evidence cited included testimony from senior military officials who said Yoon ordered the arrest of National Assembly lawmakers, as well as a planning memo allegedly discussing the “disposal” of hundreds of perceived opponents—among them journalists, labor activists, and politicians.

Although no deaths occurred during the standoff, prosecutors emphasized that the absence of bloodshed was due to resistance from institutions and individuals, not restraint from the president. They argued that the true victims were the South Korean people and the constitutional order itself.

Yoon’s Defense: Authority, Not Insurrection

Yoon has categorically denied the charges. His legal team maintains that the martial law declaration was a symbolic act meant to highlight what he claimed were dangerous abuses by the opposition Democratic Party. According to Yoon, he acted within his constitutional authority as president to protect the nation from internal and external threats, including alleged North Korean influence.

Supporters on South Korea’s political right have echoed that defense, warning that criminalizing a president’s use—however controversial—of emergency powers risks setting a precedent that could weaken executive authority in future crises. Some have cast Yoon as a political martyr rather than a would-be autocrat.

A Rare and Heavy Sentence

South Korea has not carried out an execution in nearly three decades, and death sentences are widely viewed as symbolic. In a notable precedent, former dictator Chun Doo-hwan was sentenced to death in 1996 for his role in a military coup, only to have the sentence commuted to life imprisonment.

That history makes it uncertain whether the court will follow prosecutors’ recommendation when it delivers a verdict, expected in February 2026.

Political Aftershocks

The failed martial law bid reshaped South Korean politics. It led to a snap election in June 2025 that brought opposition leader Lee Jae-myung to power. His administration has emphasized the rule of law and accountability, framing the trial as proof that no one—not even a former president—is above the constitution.

For conservatives, however, the case raises deeper concerns about political retaliation and the stability of executive power in a polarized democracy.

A Test for Korean Democracy

Regardless of the outcome, the trial of Yoon Suk Yeol represents a defining moment for South Korea. It underscores the strength of its democratic institutions—but also exposes the fragility that emerges when political conflict collides with emergency powers.

As the nation awaits the court’s decision, the question looming over Seoul is not only Yoon’s fate, but how a democratic system balances accountability with restraint in times of crisis.