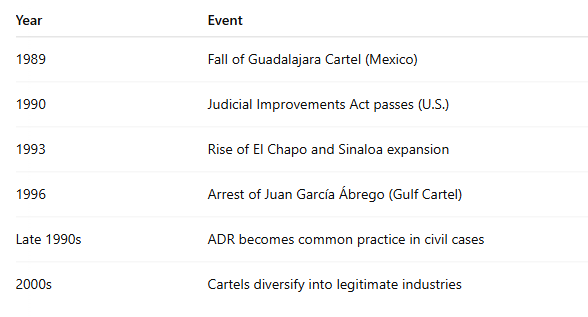

They say timing is everything. In the 1990s, two seemingly unrelated forces quietly reshaped the American landscape — and few noticed the dangerous overlap.

On one side of the border, Mexican drug cartels like Sinaloa and the Gulf Cartel launched an era of unprecedented expansion into the United States. On the other, the American legal system pivoted toward Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR), a well-intentioned but ultimately flawed movement that prioritized private settlements over public trials.

The consequences of these parallel shifts are still echoing today — in ways far more connected than we might like to admit.

The 1990s: Cartels Unleashed

The breakup of Mexico’s Guadalajara Cartel in the late 1980s unleashed a fierce competition for control of the drug trade. Two groups emerged as dominant players:

- Sinaloa Cartel:

Under the leadership of Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, Sinaloa revolutionized trafficking operations. No longer content with simply moving marijuana, Sinaloa diversified into cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine — and innovated in smuggling methods.

From underground tunnels burrowing beneath the U.S. border to maritime shipments crossing oceans, Sinaloa created an international distribution network stretching from Mexico to Europe and Asia. - Gulf Cartel:

Led by Juan García Ábrego, the Gulf Cartel also broke new ground — economically. Rather than charging a flat fee for moving Colombian cocaine across the border, García Ábrego struck a different deal: he would take 50% of every shipment.

This strategy allowed the Gulf Cartel to amass vast stockpiles of narcotics and establish footholds in U.S. cities like Houston, Chicago, and New York.

Meanwhile, García Ábrego built an empire of corruption. According to DEA reports at the time, nearly the entire Mexican Attorney General’s Office was compromised — with insiders estimating that as much as 95% of officials were on the cartel’s payroll.

By the mid-1990s, the cartels weren’t just selling drugs. They were laundering billions through legitimate businesses, political bribes, and sophisticated financial systems. Their reach was metastasizing — and America’s institutions were unprepared.

Meanwhile, in U.S. Courtrooms: A Quiet Revolution

While cartels expanded their reach, a revolution was underway in the American legal system — one that would change how justice was delivered, and how much sunlight reached the truth.

In 1990, Congress passed the Judicial Improvements Act, which formally institutionalized Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) in federal courts.

- Mediation.

- Arbitration.

- Private settlement conferences.

ADR was marketed as a solution to a clogged judicial system — a way to save money, resolve disputes faster, and free up court dockets.

On the surface, the intentions were noble. In practice, ADR often meant moving sensitive matters behind closed doors, away from the public eye, away from the rules of evidence, and away from full constitutional protections.

Critics warned that ADR lacked transparency, weakened accountability, and created a two-tiered system of justice — one for those who could afford to negotiate behind closed doors, and another for everyone else.

But few could foresee how dangerous this lack of scrutiny could become when criminal organizations entered the picture.

The Overlap: A Vulnerability Created

Here’s where the timelines cross:

- As cartels pumped narcotics, cash, and influence into the U.S.,

- America’s legal system increasingly favored confidential, expedited private proceedings over public trials.

While there is no direct evidence that Mexican drug cartels systematically exploited ADR mechanisms to launder money in the 1990s, experts have long warned that any system lacking transparency is ripe for abuse.

Confidential settlements. Private arbitrations. Out-of-court resolutions.

All provided opportunities — not necessarily for the average citizen, but for anyone with enough money and motivation to mask illegal activity behind layers of legitimate-seeming paperwork.

At the very least, the rise of ADR coincided with a period where criminal enterprises became better at blending into legitimate business channels — from real estate deals to investment firms to shell corporations. Whether ADR directly enabled cartel laundering remains a critical, unanswered question.

But the vulnerability was — and is — very real.

The Legacy: Blind Spots That Persist

Today, the consequences of this convergence still linger.

- Drug cartels continue to operate sophisticated financial networks inside the United States.

- ADR dominates many civil and family law matters, with little public scrutiny.

- Corruption scandals occasionally pierce the surface — but systemic reform remains elusive.

Most Americans never realized that while they were promised cheaper and faster justice, what they actually received was a system that increasingly privileged secrecy over transparency — and left open doors for exploitation by the powerful.

As we grapple with the modern fentanyl crisis, the laundering of illicit wealth, and the erosion of public trust in the courts, it’s worth asking hard questions:

- Did the 1990s legal reforms — however well-intentioned — accidentally aid the very forces undermining our society?

- And if so, what are we willing to do about it now?

Because when justice moves into the shadows, it’s not just criminals who thrive.

It’s corruption itself.

Author’s Note:

This investigation builds on historical records, official reports, and known timelines. While no direct smoking gun connects cartels to ADR exploitation in the 1990s, the convergence of these events created vulnerabilities that remain relevant — and troubling — today. Readers are encouraged to explore the historical sources and consider the importance of transparency, due process, and vigilance in protecting the integrity of our legal system.